SEBI Virtual Museum (Dharohar)

On Republic Day (Sunday, January 26), the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) launched a virtual museum (called Dharohar) on the Indian securities markets. This website has an image gallery featuring share and bond certificates from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. It also has videos of interviews with former SEBI Chairman, Whole Time Members, and others who have played an important role in the Indian securities markets. This section includes an interview with me: the interview highlights as well as the full interview are available in the virtual museum.

Some of the issues discussed in my interview are listed below along with the approximate time segment of the video where the discussion occurs:

- The evolution of the Indian securities markets (At around 0:30)

- Regulation versus supervision (At around 07:30)

- Transition from Badla to equity derivatives (At around 10:00)

- Risk management and market design in equity derivatives market (At around 15:00)

- Importance of cash market and derivative market liquidity (At around 22:30)

- Successes of equity market reforms (At around 26:00)

- SEBI Secondary Markets Advisory Committee (At around 30:00)

- Corporate bond market (At around 37:00)

- Employee Stock Option (ESOP) regulation (At around 42:30)

- Disclosure best practices (At around 49:00)

- Impact of technology on markets and regulation (At around 54:00)

- Equities as a long term investment (At around 1:00:00)

- Role of advisory committees (At around 1:03:30)

Posted at 6:38 pm IST on Wed, 29 Jan 2025 permanent link

Categories: miscellaneous

My conversation with Sashi Krishnan for NISM Masterclass

Last month, Sashi Krishnan, Director, National Institute of Securities Markets (NISM) interviewed me for the NISM Masterclass series in a wide ranging conversation that lasted more than an hour. The video of this conversation has now been published at the NISM website.

Some of the issues discussed are listed below along with the approximate time segment of the video where the discussion occurs:

- The 1990s debate in India about the abolition of the Badla system, and its replacement with equity derivatives. (At around 0:03:00)

- The "excessive" size of the Indian equity derivatives market. (At around 0:06:30)

- The lack of an exchange traded interest rate derivative market in India, the failure of Indian institutions to contribute to market development, and the role of speculators in providing liquidity. (At around 0:11:00)

- The growth in India's stock market capitalization and its ratio to GDP. (At around 0:19:30)

- The boom in the IPO market in India in the last year or so. (At around 0:23:00)

- Investment restrictions on insurance companies and pension funds. (At around 0:28:00)

- Mis-selling and buyer beware. (At around 0:30:30)

- Efficient Markets Hypothesis and factor investing. (At around 0:34:00)

- Passive investing. (At around 0:43:45)

- 24/7 securities trading. (At around 0:48:30)

- Bitcoin and the Blockchain. (At around 0:50:00)

- India's potential for 8-10% growth. (At around 0:59:30)

- The relationship between GDP growth and stock market performance. (At around 01:03:00)

- Financial literacy. (At around 01:05:45)

Posted at 9:17 pm IST on Mon, 6 Jan 2025 permanent link

Categories: miscellaneous

Banking before the modern era

The history of banking in the modern era (last 500 years or so) is reasonably well known. However, I knew very little of banking before that era (except that it was dominated by the Italians). Two recent books helped me understand pre-modern banks a little better:

Mehmet Baha Karan, Wim Westerman, and Jacob Wijngaard (2024) A history of banks: from the Knights Templar to the present era, Springer Cham.

Zannoni, Paolo (2024), Money and promises: seven deals that changed the world. Columbia University Press.

Only the first couple of chapters of these books deal with the pre-modern or medieval era, and I found these chapters a little sketchy, but they motivated me to probe a little deeper into this subject. Both these books cited a few papers on the subject, and I found several more through my own searches.

My understanding based on all this is that (a) there were arguably some enterprises resembling deposit banks in republican and imperial Rome two millenia ago (Harris, 2006), (b) the Knights Templar were in some sense a deposit bank in the 12th century (Ferris, 1902), and (c) there were certainly many deposit banks in Italy from around the 13th century (Roberds and Velde, 2014; Ugolini, 2020; and Usher, 1934). However, Usher does not believe that any of these were banks in the real sense of the word, as according to him, the "lending of credit" is the essential function of the banker:

The lending of coined money, with or without interest, merely transfers purchasing power from one person to another. The mere acceptance of deposits of coined money involves no banking activity, even if the money is used in trade. In such a case, too, there is merely a transfer of purchasing power. Banking begins only when loans are made in bank credit.

Usher also believes that the negotiable instrument is essential for a true bank, as it is the negotiable instrument that makes a bank an issuer of money. He points out that negotiable instruments like the cheque became widespread only in the sixteenth century, and commercial law exhibited a positive bias in favour of verbal contracts all through the fifteenth century. De Roover (1943) also highlights the use of oral orders in lieu of written checks in medieval banking.

Munro (2003) emphasizes the importance of usury laws that impeded borrowing and lending, and points out that these restrictions were relaxed only in the 16th century. If this is true, India should have had an advantage in the development of banking in pre-modern times because of the absence of usury laws even under Islamic rulers (Habib, 1964). Habib mentions that during the Delhi Sultanate, when a Muslim theologian condemned one of Muhammad Tughluq's policies on the ground that the State might earn an usurious gain from the transaction, the Sultan simply executed the hapless scholar, and continued to implement the policy. Unfortunately, most of the material that I have seen on banking in India does not discuss the pre-Mughal period. So I am unable to throw any light on the hypothesis that India was a more conducive environment for the emergence of banks in that period.

An interesting question is whether recent developments in the field may be taking us back full circle to something resembling pre-modern banking. With the relentless growth of bond markets and the emergence of private credit, lending is increasingly moving out of banks to long term investors. As this trend continues, banks may start becoming narrow banks. A few decades from now, banks may not look very different from the deposit banks of the pre-modern era. The type of banking that flourished from the 16th to the 20th century might then be seen as an aberration caused by immature financial markets and underdeveloped non bank institutions.

References

De Roover, R., 1943. The lingering influence of medieval practices. The Accounting Review, 18(2), pp.148-151.

Ferris, E., 1902. The financial relations of the Knights Templars to the English crown. The American Historical Review, 8(1), pp.1-17.

Habib, I., 1964. Usury in medieval India. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 6(4), pp.393-419.

W. V. Harris, 2006, A Revisionist View of Roman Money, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 96 (2006), pp. 1-24

Munro, J.H., 2003. The medieval origins of the financial revolution: usury, rentes, and negotiability. The International History Review, 25(3), pp.505-562.

Roberds, William and Velde, Francois R., Early Public Banks (February 11, 2014). FRB of Chicago Working Paper No. 2014-03, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2399046 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2399046

Ugolini, S., 2020. The historical evolution of central banking. Handbook of the History of Money and Currency, pp.835-856.

Usher, A.P., 1934. The origins of banking: the primitive bank of deposit, 1200–1600. The Economic History Review, 4(4), pp.399-428.

Posted at 2:22 pm IST on Fri, 3 Jan 2025 permanent link

Categories: banks, financial history, interesting books

Gamestop and Engine No 1

I have been thinking about parallels between two surprising David versus Golaith episodes in the US capital market during 2021 which appear on the surface to be totally different and unrelated.

The first was the GameStop saga in which retail investors coordinated on Reddit (r/wallstreetbets) to drive up the stock price of a struggling company by several thousand percent. I blogged about this event at that time here and here. In short, many retail investors hated the big hedge funds who were short selling GameStop and hammering its stock price, and these retail investors came together on Reddit to engineer a short squeeze that inflicted heavy losses on these hedge funds.

The second was the successful proxy fight waged by the activist hedge fund Engine No 1 against ExxonMobil. This fund succeeded in getting three of their nominees elected to ExxonMobil's board though it owned only 0.02% of ExxonMobil's stock. Engine No 1 achieved its victory by gaining the support of major proxy advisory firms and many of the large institutional investors while individual shareholders tended to favor the company’s nominees. ("How Exxon Lost a Board Battle With a Small Hedge Fund", New York Times, May 28, 2021).

The first similarity that I see is that both demonstrate the importance of memes in the world of finance. GameStop itself is described as a meme-stock in a pejorative sense. But there is nothing pejorative about meme as originally defined in Richard Dawkins' The Selfish Gene. Memes in this sense are similar to narratives (as in Shiller's Narrative Economics), and they have a very significant effect on financial markets at least till the meme fades away. Climate change is as much a meme in this sense as GameStop.

The second similarity is that both these episodes raise tricky issues about assessing the rationality of the key protagonists. In the case of GameStop, the first impression of most observers is that of irrational investors driving prices far away from fundamentals. But my blog post at that time argued that rationality in economics requires only rational pursuit of one's goals, and does not demand that the goals be rational as perceived by somebody else. From this perspective, the Redditors pursued their goals quite rationally, efficiently and successfully. These actions might have been injurious to their wealth, but economic rationality does not require wealth maximization. Warren Buffet can give away most of his wealth through his philanthropy and still be a highly rational investor.

In the case of Engine No 1 also, there is a troubling question of rationality. The amount that this fund spent on the proxy fight was a very large fraction of the entire value of its investment in ExxonMobil. (Initially, it was thought that the amount spent by Engine No 1 on the proxy fight equalled 85% of the cost of its 0.02% stake in ExxonMobil, but subsequent estimates suggest that it might have been only 40%). The appreciation of ExxonMobil attributable to the proxy fight would almost certainly be far lower than even the lower estimate because the bulk of the stock price movement would be due to changes in the oil price cycle. Moreover, the proxy fight was quite close and even just before the voting, Engine No 1 could have expected only about 50% chance of success. When they began the proxy fight, the probability of success would have been far lower. It is hard to imagine a rational calculation in which initiating the proxy fight would have been a positive expected value bet for Engine No 1.

But there is a deeper level at which the proxy fight was quite rational. The proxy fight was a wonderful boost to the reputation and visibility of Engine No 1. It seems obvious to me that the same amount of money spent on advertising would have been far less effective in establishing it as a serious player in the hedge fund business. Engine No 1 appears to have pivoted away from climate activism and from activism in general, but it does run an active investment business which continues to benefit from the aura gained during that proxy fight.

The third similarity that I see is highly speculative and is probably something that finance professors like me should leave to psychologists and sociologists to think about. I wonder whether the Covid-19 pandemic led to a temporary change in people's goals and aspirations. Was there a temporary increase in the willingness of people to sacrifice short term self interest (narrowly defined) in favour of larger goals? As the pandemic faded away, and the battle between humanity and the virus gave way to wars between humans and humans, did this burst of altruism also decay giving way to the renewed ascendancy of narrow pecuniary rationality? If there is any truth in this wild speculation of mine, the rise and fall of meme stock investing and the rise and fall in ESG investing would both seem to me to fit in well with this explanation.

Posted at 1:05 pm IST on Wed, 11 Dec 2024 permanent link

Categories: behavioural finance

Code is Law versus Contract is Law

“Code is Law” has been one of the slogans of the blockchain and cryptocurrency world. The core belief is that the intentions of the parties do not matter, and the only thing that matters is the actual software code that implements these intentions. Even if somebody finds a bug in the code, and exploits it to make money, “Code is Law” would regard this as a legitimate activity. The correct response to such a hack is to write better code in future.

Mainstream finance does not accept this idea. In 2022, Avi Eisenberg hacked Mango Markets, a decentralized finance (DeFi) trading platform on the Solana blockchain, and took out over $100 million. He claimed that he was an applied game theorist who had simply implemented a highly successful trading strategy that fully conformed to the rules of Mango Markets as embodied in their code (“Code is Law”). A jury did not buy this argument and convicted him for market manipulation in April this year. Courts obviously take into account the intentions of the parties.

Or do they? This week the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed the lower court’s ruling confirming an arbitration award that required the seller of a supermarket chain to pay the private equity buyers twice the purchase price. No that is not a typo. It was not the buyer paying the seller, but the seller paying the buyer, and that too twice the purchase price. The Chancery Court agreed that “the outcome that the Buyer achieved in this case was ... economically divorced from the intended transaction,” and the arbitrator also expressed a similar view. But Delaware law embraces strict contractarianism - “Contract is Law.” The arbitrator would not consider the intentions of the parties, and the courts would not step in either.

The US Justice Department and the CFTC prosecuted Essenberg for market manipulation. Should and would the Justice Department and the SEC prosecute the private equity buyers for market manipulation?

How is “Contract is Law” different from “Code is Law?” Do not the moral hazard argument work equally well in both cases? If “Contract is Law” encourages all parties to draft better contracts and read them more carefully, “Code is Law” encourages everyone to write better code and review them more carefully.

Posted at 2:18 pm IST on Thu, 14 Nov 2024 permanent link

Categories: blockchain and cryptocurrency, law, manipulation

Art of risking everything

In my last post about my resuming my blog, I asked for suggestions on the scope and nature of the blog. Several comments requested me to write about the books that I have been reading recently, and I have embraced this idea. The caveat is that these would not be book reviews, but would be my reflections on what I took away from the book. Moreover, they would be highly opinionated, and would largely be about finance even if the book is not about finance.

Today’s book is On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything1 by Nate Silver, author of The Signal and the Noise and famous mostly for founding the election forecasting site FiveThirtyEight. This book is not about finance at all, and I had great difficulty wading through four uninteresting chapters about gambling and poker before getting to the relatively small bit of finance in the middle. The finance portion is mainly about venture capital and cryptocurrency.

Underlying all the disparate chapters in the book is the broader theme about attitude towards risk, and this is of great interest to any finance professional. Nate Silver begins by distinguishing between the “river” and the “village”, where the people in the river are given to analytical and abstract thinking and are competitive and risk tolerant (This is a bit of an oversimplification because Silver mentions a few other cognitive and personality traits also). The difficulty with this characterization is that in finance, attitude towards risk is not binary (risk averse versus risk tolerant), but encompasses a broad spectrum of risk aversion coefficients. The theoretical range of the Arrow-Pratt measure of relative risk aversion2 is from negative infinity to positive infinity, but for most people, it probably lies between 1 and 10. Therefore, a finance professional would quite likely regard a risk aversion coefficient of around unity as being quite risk tolerant, though technically any risk aversion coefficient greater than zero signifies risk aversion. Zero represents risk neutrality and negative coefficients signify risk seeking.

At certain points in the book, Silver seems to imply that somebody with a risk aversion coefficient of unity or even somewhat higher belongs in the “river”. For example, twice he says that most gamblers regard the Kelly criterion3 as being too aggressive and prefer bets of only quarter to half of the Kelly bet size. The Kelly criterion corresponds to a risk aversion coefficient of exactly unity, and so this implies that most gamblers have risk aversion coefficients significantly above unity. At other points in the book, Silver seems to suggest that people in the river seek out any positive expected value opportunities which suggest risk neutrality (a coefficient of zero) if not risk seeking. Of course, Pratt showed that a rational person would take at least a tiny slice of any positive expected value opportunity. This is because risk aversion (which is a second order phenomenon) can be ignored for infinitesimal bets. Perhaps, this is what Silver means, but, in that case, the logic applies only to highly divisible bets.

At times, I got the feeling that all expected utility maximizers are in Silver’s “river”, and only people confirming to prospect theory or behavioural finance are in his “village”, but Silver mentions prospect theory only in a footnote and in the glossary, and he does not describe this as a “village” trait. He does emphasize that “river” people perform Bayesian calculations, and the distortion of probabilities in prospect theory would perhaps not be “riverine”. What I do not understand after reading the whole book is whether a highly rational expected utility maximizer with a risk aversion coefficient of 25 belongs in the “river” or not. The problem is that while Silver praises river people for “decoupling” (keeping different aspects of a problem separate), he works throughout with a tight coupling of the cognitive and personality traits of the “river” people.

Silver cheerfully admits to being a “river” person, and often suggests that the “river” is winning. But there is some ambiguity about what it means for the “river” to win. Does it mean that the “river” people collectively win, or that the typical or average “river” person wins? This distinction is illustrated by Silver’s discussion of the Kelly criterion on pages 396-400 (if you do not have the book in front of you, Brad Delong’s blog post which Silver cites in an end note provides a very similar treatment). Mathematically, the Kelly criterion maximizes long run wealth. The intuition is that when you have positive expected value investment opportunities, you definitely want to bet on them (recall Pratt’s result that the optimal bet size is never zero), but if you bet too much, you may be ruined and then you lose the opportunity to make more positive value bets in future. Long run optimization must therefore ensure long run survival to allow wealth to compound over those long horizons, and this leads to an optimal size of the bet.

Imagine three groups of people: (a) the “village” whose inhabitants do not participate in risky assets at all because of behavioural reasons or infinite risk aversion, (b) the Kelly “river” filled with venture capitalists who bet the optimal fraction of their wealth at each round on various risky (positive expected value) ventures, and (c) the risk neutral “river” comprising risk neutral founders who bet their entire wealth on their respective risky (positive expected value) ventures. Note that this is my analogy, and Silver does not use this interpretation during the discussion on Kelly. Most inhabitants of the Kelly “river” will outperform the “village” handsomely because Kelly ensures high returns with negligible chance of being ruined. But the risk neutral “river” will outperform both of the others on average. Almost everybody here would be ruined, but the one person who managed to survive would make so much money that the average wealth of the risk neutral “river” will be far higher than even the Kelly “river”. (For simplicity, I assume that the different ventures are independent.)

If you care more about the group rather than yourself, then the risk neutral “river” is possibly optimal in the sense that collectively this group is better off than the others. But the “river” people were supposed to be competitive and not collectivist and socialistic. So it is not clear whether this is the “river” at all. Brad Delong’s blog post uses the multiple universes interpretation of quantum physics to suggest that even if you are ruined in this universe, there is a parallel you in some other universe who has made it big. I think that this is closer to theology than to finance.

Silver’s book does have a long discussion about venture capitalists and founders and seems to suggest that the venture capitalists have to be rational, while the founders have to be irrational to willingly accept large probability of ruin. I do not agree because as Broughman and Wansley4 have pointed out, risk sharing between the VC and the founder can ensure that founders do well even when the venture fails. Recall Adam Neumann making a fortune even as WeWork went bust.

At the end of the book, I was left with the impression that Silver wants to self identify not with cold blooded rational calculators, but with daring risk takers, and this tendency colours a great deal of the discussion in the book. This attitude is best captured in the last of his thirteen habits of successful risk-takers: “13. Successful risk-takers are not driven by money. They live on the edge because it’s their way of life.” Nevertheless, by ignoring his personal preferences, I could learn many interesting things from the book, and some of these ideas are useful in finance as well. The “river” and the “village” are I think a useful way of thinking about classical and behavioural finance even if that was not what Silver had in mind at all.

Notes and references:

-

Nate Silver. 2024. On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything. Penguin Books. ↩

-

The Arrow-Pratt measures of absolute and relative risk aversion were enunciated in: Pratt, J.W., 1964. “Risk Aversion in the Small and in the Large”. Econometrica, 32(1/2), pp.122-136. This remains in my view a better treatment of this subject than most modern finance textbooks. ↩

-

The Kelly criterion specifies the optimal bet size that maximizes long run wealth. The optimality of this criterion was proved in: Kelly, J.L., 1956. “A new interpretation of information rate”. The Bell System Technical Journal, 35(4), pp.917-926. It was Ed Thorpe who popularized the Kelly Criterion in gambling and in finance (see Fortune’s Formula) ↩

-

Broughman and Wansley argue that founders are reluctant to gamble because they bear firm-specific risk that cannot be diversified. VCs therefore offer an implicit bargain in which the founders pursue high-risk strategies and in exchange the VCs give founders early liquidity when their startup grows, job security when it struggles, and a soft landing if it fails. Their paper is: Brian J. Broughman & Matthew T. Wansley. 2023. “Risk-Seeking Governance”, Vanderbilt Law Review 1299. ↩

Posted at 1:36 pm IST on Wed, 30 Oct 2024 permanent link

Categories: behavioural finance, interesting books, risk management

Resuming my blog

My blog has been suspended for nearly four years now. My term as a member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the Reserve Bank of India ended early this month, and I am now looking forward to resuming my blog.

However, posting is likely to be erratic for the next couple of months as I would be making a career transition subsequent to my retirement from the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad at the end of this calendar year. This career transition has yet to be finalized, and so I am unable to provide any details at this stage.

I am also contemplating some changes in the scope of the blog like a bit more of macro finance and perhaps more of finance pedagogy. Please feel free to make suggestions in the comments.

Posted at 11:27 am IST on Tue, 22 Oct 2024 permanent link

Categories: miscellaneous

Migration of my website and blog

My website and blog have now been migrated to my own domain https://www.jrvarma.in/. Earlier, they were hosted at my Institute's website at https://www.iima.ac.in/~jrvarma/ and https://faculty.iima.ac.in/~jrvarma/.

My blog has been suspended for some time and is likely to remain suspended till October 2024. However, all old blog posts (along with the comments) have been migrated to the new location (https://www.jrvarma.in/blog/). There is also an rss feed and an atom feed, though these will be useful only when the blog resumes.

There is no change in the WordPress mirror https://jrvarma.wordpress.com/, and so those who were following my blog at WordPress can ignore this migration.

Posted at 1:20 pm IST on Mon, 14 Nov 2022 permanent link

Categories: miscellaneous

Revisiting Jensen’s Agency Costs of Overvalued Equity

After the dot com bust, Michael C. Jensen wrote a paper comparing overvalued equity to managerial heroin:

When a firm’s equity becomes substantially overvalued it sets in motion a set of organizational forces that are extremely difficult to manage — forces that almost inevitably lead to destruction of part or all of the core value of the firm. (Jensen, M.C., 2005. Agency costs of overvalued equity. Financial management, 34(1), pp.5-19.)

What is amazing about the equity overvaluation created by meme-based investing (the reddit and Robinhood retail investors) is that far from destroying companies, it is resuscitating companies that were earlier presumed to be beyond salvation. On Tuesday, AMC Entertainment Holdings, Inc. raised $230 million by selling 1.7% of its equity to a hedge fund, Mudrick Capital, which promptly turned around and sold the shares into the market at a profit. AMC which claims to be “the largest movie exhibition company in the United States, the largest in Europe and the largest throughout the world with approximately 950 theatres and 10,500 screens across the globe” was struggling because of the pandemic and had plenty of uses for the money: it stated that:

The cash proceeds from this share sale primarily will be used for the pursuit of value creating acquisitions of additional theatre leases, as well as investments to enhance the consumer appeal of AMC’s existing theatres. In addition, with these funds in hand, AMC intends to continue exploring deleveraging opportunities.

With our increased liquidity, an increasingly vaccinated population and the imminent release of blockbuster new movie titles, it is time for AMC to go on the offense again.

The prospectus related to this sale described the risks very clearly:

it is very difficult to predict when theatre attendance levels will normalize, which we expect will depend on the widespread availability and use of effective vaccines for the coronavirus. However, our current cash burn rates are not sustainable.

during 2021 to date, the market price of our Class A common stock has fluctuated from an intra-day low of $1.91 per share on January 5, 2021 to an intra-day high on the NYSE of $36.72 on May 28, 2021 and the last reported sale price of our Class A common stock on the NYSE on May 28, 2021, was $26.12 per share.

the market price of our Class A common stock has experienced and may continue to experience rapid and substantial increases or decreases unrelated to our operating performance or prospects, or macro or industry fundamentals, and substantial increases may be significantly inconsistent with the risks and uncertainties that we continue to face; our market capitalization, as implied by various trading prices, currently reflects valuations that diverge significantly from those seen prior to recent volatility and that are significantly higher than our market capitalization immediately prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and to the extent these valuations reflect trading dynamics unrelated to our financial performance or prospects, purchasers of our Class A common stock could incur substantial losses if there are declines in market prices driven by a return to earlier valuations;

AMC shares rose after this capital raise, and AMC followed up on Thursday with a at-the-market offering of an additional 2.3% of its shares that raised $587 million at a price of $50.85 per share. The prospectus came with an even more blunt disclosure:

We believe that the recent volatility and our current market prices reflect market and trading dynamics unrelated to our underlying business, or macro or industry fundamentals, and we do not know how long these dynamics will last. Under the circumstances, we caution you against investing in our Class A common stock, unless you are prepared to incur the risk of losing all or a substantial portion of your investment.

Michael Jensen considered the possibility that capital raising could eliminate overvaluation, but ruled it out:

Some suggest that one solution to the problem of overvalued equity is for the firm to issue overpriced equity and pay out the proceeds to current shareholders. I have grave doubts that this is a sensible or even workable solution for several reasons.

AMC has shown that Jensen’s fears about regulatory obstacles and disclosure requirements were totally misplaced. But Jensen also raised an ethical issue which goes to the very foundations of corporate finance:

I believe it is impossible to create a system with integrity that is based on the proposition that it is ok to exploit future shareholders to benefit current shareholders. I realize this is not a generally accepted proposition in today’s finance profession, not even among scholars, but it would take us too far from my topic today to discuss it thoroughly.

I am not however impressed by this ethical argument because capitalism depends on allowing trades between two parties with differing beliefs and expectations without worrying that one party is mistaken and is therefore being exploited by the other. I see the AMC capital raises as capitalism working nicely to harmonize heterogeneous beliefs and expectations through the mechanism of mutually beneficial trades.

Posted at 4:07 pm IST on Fri, 4 Jun 2021 permanent link

Categories: bubbles, corporate governance

Lessons from the Hertz Bankruptcy for Indian Bankruptcy Law

The pandemic induced Hertz bankruptcy in the US has upended a whole lot of what we thought we knew about how to run a bankruptcy proceeding.

What we used to think

It is optimal to complete the bankruptcy as quickly as possible. An insolvent business is like a melting ice cube that would lose all value if the bankruptcy were not sorted out very quickly. The gold standard of this approach was the Lehman bankruptcy in which the judge approved a sale agreement (filled with handwritten corrections) after midnight at the end of a chaotic day-long hearing. In India, the law mandates tight deadlines for the whole process, but it has not proved possible to adhere to them.

The big players know best and everybody else is basically a nuisance. In India, this is written into the law where a bunch of supposedly omniscient and incorruptible “financial creditors” have complete control over the proceedings and everybody else is left to their mercy (I have blogged about this here, here, and here). In the US, this is thankfully only an unwritten law, but there is little doubt that the big distressed debt investors are in charge.

The Absolute Priority Rule (APR) is the ideal way to distribute value: the sale proceeds or liquidation value should be distributed to creditors in the order of their seniority. This implies that the junior creditors as well as the shareholders often get wiped out. Bankruptcy courts do find ways to bypass the APR, but, to a first approximation, it more or less determines the allocation of value. In India, the APR is twisted to prioritize financial creditors over operational creditors, but in that modified form, it holds sway.

What Hertz taught us

Hertz reminds us that there are many exceptions to the received wisdom that guides our thinking and statutes about bankruptcy.

Hertz is likely to realize substantial value only because the bankruptcy court has run the proceedings at a leisurely pace allowing a sequence of ever higher bids to emerge as the pandemic abated. In some ways, this was an accident caused by the unplanned bankruptcy filing that was not accompanied by a Debtor in Possession (DIP) financing package, but it is at least partly due to the incessant prodding by the shareholders’ committee.

The retail shareholders who bought Hertz stock after it filed for bankruptcy were ridiculed at the time, but they now seem to have been at least partly right. The latest bids show that the shareholders will get some payout in bankruptcy after all. Some commentators have even compared the retail shareholders’ optimism to Bill Ackman’s legendary exploits during the General Growth Properties (GGP) bankruptcy.

Some scholars are now arguing that the Hertz bankruptcy exposes problems with the Absolute Priority Rule and that a Relative Priority Rule makes more sense. Casey and Macey argue that the option value of junior creditors and shareholders should not be extinguished as in the APR, but they should be allowed to recover that value as a payout in the bankruptcy proceeding, a stake in the reorganized firm, or a warrant that allows them to buy shares of the reorganized firm at a predetermined exercise price at a future date (see Casey, A.J. and Macey, J.C., 2020. The Hertz Maneuver (and the Limits of Bankruptcy Law). U. Chi. L. Rev. Online, p.1. available at https://lawreviewblog.uchicago.edu/2020/10/07/casey-macey-hertz/). In fact, I must acknowledge that Casey and Macey as well as Best Interest Blog inspired many of the ideas in this post.

Posted at 1:20 pm IST on Mon, 3 May 2021 permanent link

Categories: bankruptcy, investment

Archegos and marking academic literature to reality

Last week, Bill Hwang’s family office, Archegos, imploded as it was unable to meet the margin calls emanating from steep declines in the prices of stocks that Hwang had bought with huge leverage. Mark to market is a very powerful discipline that spares nobody however rich or powerful. This ruthless discipline makes financial markets self-correcting unlike many other social institutions.

Academic literature in particular is much more insulated from the discipline of mark to reality. Old papers discredited by subsequent developments or even subsequent research continue to be cited and quoted (this is the replication crisis in economics and finance). To borrow accounting terminology, the academic community tends to carry the old literature at historical cost without sufficiently stringent periodic impairment tests.

There is a large stream of finance and accounting literature which is probably badly impaired by last week’s developments. I refer to the literature that uses percentage of institutional shareholding in a company as a proxy for various things including corporate governance. What we are learning now is that Archegos used over the counter derivatives like swaps and contracts for differences to invest in a range of companies with very high leverage. The banks who sold these derivatives to Archegos bought shares in the companies to hedge the derivatives that they had sold. The shareholding pattern of these companies would then show the Archegos counterparties (banks) as the principal shareholders of these companies though in economic terms, the real owner of the shares was Archegos. Media reports suggest that this includes companies which were targeted by short sellers (and presumably had corporate governance concerns).

In the case of these companies with possibly dubious corporate governance, academics and investors might have been reassured on observing that say two-thirds of the shares were owned by institutions without realizing that much of the holding was the family office of a person who had committed insider trading. I think this is another illustration of Goodhart’s law: “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.” The lesson that the academic literature must learn from that law is that the longer established a proxy measure is, the more ruthlessly one must apply an impairment test and mark it to reality.

Posted at 9:02 pm IST on Wed, 31 Mar 2021 permanent link

Categories: arbitrage, banks, failure, regulation

Stock Exchange Outages

A month ago, the National Stock Exchange (NSE), India’s largest stock exchange, suffered a software glitch and suspended trading about four hours prior to the scheduled end of the trading session. As the clock ticked close to the scheduled end of the trading day, there was no news about resumption of trading, and stock brokers decided to close out the outstanding positions of their clients on the other exchange (BSE) to avoid exposure to overnight price risk. About 13 minutes before scheduled close of the trading session, the NSE announced that normal market trading would resume 15 minutes after the scheduled close and would continue for 75 minutes thereafter. Yesterday, the NSE put out a self congratulatory press release providing some details of what happened on February 24, 2021. This is a vast improvement on the very limited information that they released a month ago (24th morning, 24th afternoon and 25th).

It appears that the regulators are also investigating the matter and, perhaps, much effort will be expended on apportioning blame between NSE and its various technology vendors. I wish to take a different approach here and argue that the regulators should simply lay down an downtime target. The computing industry works with Four Nines (99.99%) availability (less than an hour of downtime a year) and Five Nines (99.999%) availability (about five minutes of downtime a year). Let us assume that Five Nines is out of reach for stock exchanges and settle for Four Nines. There would then be no penalty for the first hour of downtime permitted under Four Nines and the penalty per hour thereafter would be calibrated so that the entire profits of the stock exchange are wiped out if the availability drops below Three Nines (99.9%) corresponding to a downtime of about nine hours per year.

Based on the most recent financial statements of the NSE, the penalty for that exchange would be about Rs 2.2 billion (around $30 million) per hour beyond the first hour. The penalty is designed to be large enough to ensure that the shareholders of the exchange weep when the exchange suffers an outage. They would then force the management to invest in technology, and also design management bonuses in such a way that they all get zeroed out when there is a large outage. The exchange would then negotiate large penalty clauses with their vendors so that if a telecom link fails, the telecom company pays a large penalty to the exchange. That provides the incentives to the telecom company to build redundancies. The regulators do not have to do any root cause analysis or apportion blame; they just have to collect the penalty, and use that to compensate the investors.

The other thing that the regulators need to do is to provide greater predictability about resumption of trading after a glitch. I would propose a simple set of rules here:

- If an exchange has suffered an outage and has not resumed trading one hour before the scheduled end of the trading session, all other exchanges (which have not suffered an outage) would extend their trading session by two hours automatically.

- If the exchange suffering the outage is able to resume trading not later than half an hour after the regular closing time, its trading session will also extend two hours beyond the regular closing time.

- If an exchange does not resume trading even half an hour after the scheduled closing time, it is not permitted to resume trading that day.

Stock exchange software glitches have been a favourite topic on this blog as long back as fifteen years ago and I suspect that they will continue to provide material for this blog for many, many years to come.

Posted at 5:07 pm IST on Tue, 23 Mar 2021 permanent link

Categories: exchanges, regulation, technology

Does Gamestop have a negative beta?

TL;DR: No!

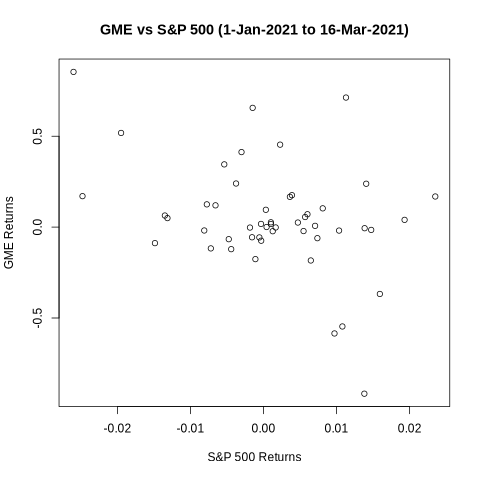

The internet is a wonderful place: it knows that I have posted on Zoom’s negative beta and it also knows that I have posted on Gamestop and r/wallstreetbets. So it quite correctly concludes that I would have some interest in whether Gamestop has a negative beta. Yesterday, I received a number of comments on my blog on this question and my blog post also got referenced at r/GME. According to r/GME, several commercial sources (Bloomberg, Financial Times, Nasdaq) that provide beta estimates are reporting negative betas for Gamestop (GME).

I began by running an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression of GME returns on the S&P 500 returns. Using data from the beginning of the year till March 16, I obtained a large negative beta which is statistically significant at the 1% level. (If you wish to replicate the following results, you can download the data and the R code from my website).

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

beta -10.54182 3.84200 -2.744 0.00851

The next step is to look at the scatter plot below which shows points all over the space, but does give a visual impression of a negative slope. But if one looks more closely, it is apparent that the visual impression is due to the two extreme points: one point at the top left corner showing that GME’s biggest positive return this year came on a day that the market was down, and the other point towards the bottom right showing that GME’s biggest negative return came on a day that the market was up. These two extreme points stand out in the plot and the human eye joins them to get a negative slope. If you block these two dots with your fingers and look at the plot again, you will see a flat line.

Like the human eye, least squares regression is also quite sensitive to extreme observations, and that might contaminate the OLS estimate. So, I ran the regression again after dropping these two dates (January 27, 2021 and February 2, 2021). The beta is no longer statistically significant at even the 10% level. While the point estimate is hugely negative (-5), its standard error is of the same order.

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

beta -4.97122 3.62363 -1.372 0.177

However, dropping two observations arbitrarily is not a proper way to answer the question. So I ran the regression again on the full data (without dropping any observations), but using statistical methods that are less sensitive to outliers. The simplest and perhaps best way is to use least absolute deviation (LAD) estimation which minimizes the absolute values of the errors instead of minimizing the squared errors (squaring emphasizes large values and therefore gives undue influence to the outliers). The beta is now even less statistically significant: the point estimate has come down and the standard error has gone up.

Estimate Std.Error Z value p-value

beta -2.7999 5.0462 -0.5548 0.5790

Another alternative is to retain least squares but use a robust regression that limits the influence of outliers. Using the bisquare weighting method of robust regression, provides an even smaller estimate of beta that is again not statistically significant.

Value Std. Error t value

beta -1.5378 2.3029 -0.6678

Commercial beta providers use a standard statistical procedure on thousands of stocks and have neither the incentive nor the resources to think carefully about the specifics of any situation. Fortunately, each of us now has the resources to adopt a DIY approach when something appears amiss. Data is freely available on the internet, and R is a fantastic open source programming language with packages for almost any statistical procedure that we might want to use.

Posted at 2:47 pm IST on Wed, 17 Mar 2021 permanent link

Categories: CAPM, investment, market efficiency

The rationality of r/wallstreetbets

Much has been written about how a group of investors participating in the sub-reddit r/wallstreetbets has caused a surge in the prices of stocks like GameStop that are not justified by fundamentals. I spent a fair amount of time reading the material that is posted on that forum and am convinced that most of these Redditors are perfectly rational and disciplined investors, and have no delusions about the fundamentals of the company.

Rationality in economics requires utility maximization, but does not constrain the nature of that utility function. It does not demand that the goals be rational as perceived by somebody else. Rationality of goals is the province of religion and philosophy: for example, Plato’s Form of the Good, Aristotle’s Highest Good, Hinduism’s four proper goals (puruṣārthas), and Buddhism’s right aspiration (sammā-saṅkappa). Economics concerns itself only with the efficient attainment of whatever goals the individual has. Even the Stigler-Becker maximalist view of economics (Stigler, G.J. and Becker, G.S., 1977. De gustibus non est disputandum. The American Economic Review, 67(2), pp.76-90) does not seek to impose our goals on anybody else, and does not require that the goals be pecuniary in nature (consider, for example, the Stigler-Becker discussion about music appreciation).

It is perfectly consistent with economic rationality for a person to buy a Tesla car as a status symbol and not as a means of going from A to B. Equally, it is perfectly consistent with economic rationality for a person to buy a Tesla share as a status symbol and not as a means of earning dividends or capital gains. Buddha and Aristotle might take a dim view of such status symbols, but the economist has no quarrel with them.

It is in this light that I find the Redditors at r/wallstreetbets to be highly rational. There is a clear understanding and Stoic acceptance of the consequences of their investment decisions. In this sense, there is greater awareness and understanding than in much of mainstream finance. When Redditors knowingly pay prices far beyond what is justified by fundamentals in the pursuit of non pecuniary goals, they are only indulging in a more extreme form of the behaviour of an environment conscious investor who knowingly buys a green bond at a low yield.

There is overwhelming evidence throughout r/wallstreetbets that these Redditors are focused on non pecuniary goals:

/r/wallstreetbets is a community for making money and being amused while doing it. Or, realistically, a place to come and upvote memes when your portfolio is down.

Yo, health check time: Get proper sleep, Eat proper food, Stretch occasionally, HYDRATE. I’m sure we’ve all been glued to our screens all week, but please make sure you take care of yourselves.

There is a crystal clear understanding that most trades will lose money:

Buy High Sell low - what you do as a newcomer.

First one is free - A phenomena where you are so retarded and don’t know what the [expletive deleted] your doing you somehow make money on your first trade.

… if you don’t know any of this there is really no reason for you to be throwing 10k at weeklies you’ll lose 99% of the time.

We don’t have billionaires to bail us out when we mess up our portfolio risk and a position goes against us. We can’t go on TV and make attempts to manipulate millions to take our side of the trade. If we mess up as bad as they did, we’re wiped out, have to start from scratch and are back to giving handjobs behind the dumpster at Wendy’s.

… and also for the most part, they’re playing with their own money that they can actually afford to lose even if it hurts for a year or two.

Options are like lottery tickets in that you can pay a flat price for a defined bet that will expire at some point.

Indeed mainstream regulators could borrow some ideas from r/wallstreetbets on how to disclose risk factors in an offer document. When a risky company does an IPO, a prominent disclosure on the front page “This IPO was created for you to lose money” would be far better than the pages and pages of unintelligible risk factors that nobody reads.

Posted at 8:19 pm IST on Sun, 31 Jan 2021 permanent link

Categories: investment, market efficiency

SPACs and Capital Structure Arbitrage

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) have become quite popular recently as an attractive alternative to Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) for many startups trying to go public. Instead of going through the tortuous process of an IPO, the startup just merges into a SPAC which is already listed. The SPAC itself would of course have done an IPO, but at that time it would not have had any business of its own, and would have gone public with only the intention of finding a target to take public through the merger. Both seasoned investors and researchers take a dim view of this vehicle. Last year, Michael Klausner and Michael Ohlrogge wrote a comprehensive paper (A Sober Look at SPACs) documenting how bad SPACs were for investors that choose to stay invested at the time of the merger. Smart investors avoid losses by bailing out before the merger, and the biggest and smartest investors make money by sponsoring SPACs and collecting various fees for their effort.

As I kept thinking about the SPAC structure, it occurred to me that at the heart of it is a capital structure arbitrage by smart investors at the cost of naive investors. The capital structure of the SPAC prior to its merger consists of shares and warrants. However, in economic terms, the share is actually a bond because at the time of the merger, the shareholders are allowed to redeem and get back their investment with interest. It is the warrant that is the true equity. If the share were treated as equity, it would have a lot of option value arising from the possibility that the SPAC might find a good merger candidate, and the greater the volatility, the greater the option value. A part of the upside (option value) would rest with the warrants. But if the shares are really bonds, then all the option value resides in the warrants which are the true equity. Naive investors are perhaps misled by the terminology, and think of the share as equity rather than a bond; hence, they ascribe a significant part of the option value to the shares. Based on this perception, they perhaps sell the detachable warrants too cheap, and hold on to the equity.

From the perspective of capital structure arbitrage, this is a simple mispricing of volatility between the two instruments. Volatility is underpriced in the warrants because only a part of the asset volatility is ascribed to it. At the same time, volatility is overpriced in the shares since a lot of volatility (that rightfully belongs to the warrant) is wrongly ascribed to the share. One way for smart investors in SPACs to exploit this disconnect is to sell (or redeem) the share and hold onto the warrant, while naive investors hold on to the share and possibly sell the warrant.

Capital structure arbitrage suggests a different (smarter?) way to do this trade. If at bottom, the SPAC conundrum is a mispricing of the same asset volatility in two markets, then capital structure arbitrage would seek to buy volatility where it is cheap and sell it where it is expensive. In other words, buy warrants (cheap volatility) and sell straddles on the share (expensive volatility). At least some smart investors seem to be doing this. A recent post on Seeking Alpha mentions all three elements of the capital structure arbitrage trade: (a) sell puts on the share, (b) write calls on the share and (c) buy warrants. But because the post treats each as a standalone trade (possibly applied to different SPACs), it does not see them as a single capital structure arbitrage. Or perhaps, finance professors like me tend to see capital structure arbitrage everywhere.

Posted at 4:51 pm IST on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 permanent link

Categories: leverage

Disappointing Investigation Report on London Capital & Finance

Earlier this month, the United Kingdom Treasury published the Report of the Independent Investigation into the Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA’s) Regulation of London Capital & Finance (LCF). I read it with high expectations, but must say I found it deeply disappointing. I take perverse pleasure in reading investigation reports into frauds and disasters around the world (so long as they are in English). Beginning with Enron nearly two decades ago, there have been no dearth of such high quality reports except in my own country where unbiased factual post mortem reports are quite rare. So it was with much anticipation that I read the report on LCF which involved a number of novel issues about the risk posed by unregulated businesses carried out by regulated entities. Unfortunately, the Investigation Report did not meet my expectations: instead of providing an unbiased and dispassionate analysis of what happened, it indulges in indiscriminate and often unwarranted criticism of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). In the process, the report very quickly loses all credibility.

The LCF debacle is described well in the report of the Joint Administrators under the Insolvency Act from which this paragraph is drawn. LCF was set up in 2012 as a commercial finance provider to UK companies. From 2013, the Company sold mini-bonds, with trading significantly increasing from 2015 onwards. LCF was granted “ISA Manager” status by the UK taxation authorities (HMRC) in 2017, and LCF started selling its mini bonds under this rubric. (The necessary requirements to qualify for ISA Manager status are fairly limited; it is not a rigorous application process; and ISA Managers are not routinely monitored by HMRC). About 11,500 bond holders invested in excess of £237m in LCF mini bonds. The vast majority of LCF’s assets are the loans made to a number of borrowers a large number of whom do not appear to have sufficient assets with which to repay LCF. At present the Administrators estimate a return to the Bondholders from the assets of the Company of as low as 20% of their investment.

It is evident from the above that the most important issue in the LCF debacle is a failure of regulation rather than supervision. In the UK, mini bonds (illiquid debt securities marketed to retail investors) are subject to very limited regulation unlike in many other countries. (In India, for example, regulations on private placement of securities, collective investment schemes and acceptance of deposits severely restrict marketing of such instruments to retail investors). To compound the problem, the UK allows mini bonds to be held in an Innovative Finance ISA (IFISA). ISAs (Individual Savings Accounts) are popular tax sheltered investment vehicles for retail investors. The UK has taken a conscious decision to allow these high risk products to be sold to retail investors in the belief that the benefits in terms of innovation and financing for small enterprises outweigh the investor protection risks. While cash ISAs and Stock and Share ISAs are eligible for the UK’s deposit insurance and investor compensation scheme (FSCS), IFISAs are not eligible for this cover. Many investors may think that ISAs are regulated from a consumer protection perspective, but the UK tax department thinks of approval of ISAs as purely a taxation issue. To make matters worse, the UK has had extremely low interest rates ever since the Global Financial Crisis, and yield hungry investors have been attracted to highly risky mini bonds especially when they are marketed to retail investors under the veneer of a quasi regulated product - the IFISA. After the LCF debacle, some regulatory steps have been taken to alleviate this problem.

The Investigation Report is concerned about supervision more than regulation, and here the key issue is the regulatory perimeter issue: when an entity carries out a regulated business and an unregulated business, to what extent should the regulators examine the unregulated business. There are some financial businesses like banking where there is intrusive regulation of the unregulated business (the bank holding company). But what should the regulatory stance be on small regulated entities that carry out very limited regulated businesses (for example, confined mainly to financial marketing)? The Investigation Report simply points to the regulatory powers of the FCA to look at the unregulated business, and blithely asserts that the FCA should have been doing this routinely. This is unrealistic and would confer excessive and unacceptable powers to the financial regulators that would make them overlords of the entire society. Imagine that the publisher of the largest circulation newspaper in the country also publishes an investment newsletter that could be construed as financial promotions and is therefore regulated by the financial regulators. Do we want the regulator to have the power to take some regulatory action because it does not like the editorial stance of the newspaper? If you think that I am insane to consider such possibilities, you should examine the criminal prosecution that German financial regulators launched against two Financial Times journalists for its reporting on the Wirecard fraud. The Investigation Report does not reveal any such nuanced understanding and therefore represents a missed opportunity to improve our perspective on such matters.

Since the issuance of mini bonds is itself not a regulated activity, the role of the FCA is mainly in the area of the marketing of the bonds by LCF as a regulated entity authorized to carry on credit broking and some corporate finance activities. I would have expected the Investigation Report to focus on whether the FCA monitored LCF’s marketing (financial promotions) adequately. The Investigation Report documents that FCA received a few complaints on this, and in each instance, the FCA required changes in the website to conform to the FCA requirements. In my understanding, it is quite common for regulators worldwide to require changes in the financial promotions ranging from the font size and placement of a statement to changes in wordings to more substantive issues. The question that is of interest is where did LCF breaches lie on this spectrum (some of them were clearly technical breaches) and how did the frequency of serious breaches compare with that of other entities of similar size that the FCA regulates. Unfortunately, the Investigation Report does not provide an adequate analysis of this matter, other than saying that repeat breaches should have led to severe actions including an outright ban on LCF. That is not how regulation works or is expected to work anywhere in the world.

But these two inadequacies of analysis are not the main grounds for my disappointment with the Investigation Report. What troubled me is the repeated instances of what struck me as prima facie evidence of bias. At first, I brushed these aside and kept reading the report with an open mind, but slowly, the indicia of bias kept piling up and I began to question the objectivity and credibility of the report. At every twist and turn, wherever there was a grey area, the Investigation Report unfailingly ended up resolving this against the FCA. In the process, the credibility of the report was eroded bit by bit. By the time, I reached the end, the credibility of the report had been completely destroyed.

One of the most glaring examples of apparent bias is the discussion about a letter purported to have been sent by one Liversidge to the FCA. The only evidence for this is the statement by Liversidge that he did post the letter. Detailed search of all records at the FCA failed to find any evidence that the letter was in fact received by the FCA. One of the first things that is taught in all basic courses on logic is that it is impossible to prove a negative statement (like the statement that the letter was not received) and that is essentially what the FCA quite honestly told the Investigation Team. The Investigation Report first states that whether this letter was received or not is not relevant to the Investigation. That should have been the end of the matter. But then it goes on to make the statement that “if it had been incumbent on the Investigation to have reached a decision on this point, it would have concluded on the balance of probabilities that the Liversidge Letter was received by the FCA”. This is unreasonable in the extreme: there is no evidence other than the sender’s testimony that the letter was sent at all (let alone received), while there is some evidence that it was not received. The balance of probabilities clearly points the other way.

The Report goes to great lengths to criticize the FCA for the extended timelines of the DES programme which attempted a very significant transformation in the structure, the governance, the systems, the processes, the risk frameworks of supervision at the FCA. This was initiated around end of 2016 or early 2017 with a target completion date of March 2018, but was concluded only by December 2018. Having been involved in exercises of this kind in many organizations, I think spending a couple of years to accomplish something like this is quite reasonable (In fact it strikes me as a rather aggressive timeline). The original timeline of March 2018 appears to me to have been utterly unrealistic. The Investigation Report suggests that the FCA should instead have resorted to some “quick wins, reviews or easy fixes”. I think this suggestion is utterly misguided. “Easy fixes” is precisely the kind of thing that an organization should not do under such conditions. I think it is to the credit of the FCA Board that it did not undertake such a stupid course of action.

Actually, the FCA discovered the fraud on its own from two different angles. First, LCF filed a prospectus with the FCA and the Listing Team had a number of serious concerns on this. Second, during the course of a review of an external database (only accessible to a limited group within the FCA and on strict conditions of use) concerned with another firm, the Intelligence Team found some information on LCF and immediately escalated the matter. While the Investigation Report commends these actions, it states that if other employees at the FCA had similar levels of expertise in understanding financial statements, they would have uncovered the fraud earlier. I was aghast on reading this. Expertise in financial statements is a highly sought skill that is in short supply in the market. That the FCA manages to hire people with that skill in some critical departments is great. To expect that people in the call centre or those running authorizations would have this skill is absurd. If people with such skills thought that they may be transferred to such postings, they would probably not join the FCA in the first place.

The Investigation Report finds fault with the FCA for giving LCF permissions to carry out regulated businesses that it did not in fact use. I do not find this unusual at all. To give an analogy, the objects clause in the corporate charter (Memorandum of Association) typically contains a lot of things that the company has no intention of undertaking; it includes these things because of the severe consequences of finding that the company does not have the power under its charter to do something that has suddenly become desirable. Similarly, a regulated business would often want to have a range of regulatory authorizations that it does not expect to use. All the more so because regulators often take an restrictive view of things and take companies to task for all kinds of technical violations. For example, a stock broker who provides only execution services might want to have an advisory licence to guard against the risk that some incidental service that it provides could be regarded as advisory. Similarly, an advisory firm might worry that a minor service like collecting a document from the customer and delivering it to a stock broker might be interpreted as going beyond purely advisory services. That LCF obtained a licence but did not carry out the regulated activity is not in my view a red flag at all. The Investigation Report makes a song and dance about this despite having observed one fact that demonstrates its triviality. The FCA created a system that produced an automated alert whenever a firm did not generate income from regulated activities. Because of the high volume of automated alerts that were created as a result of this, the FCA had to allow these alerts to be closed without review!

It is indeed distressing that this deeply flawed report is all that we will ever get on this episode which raises so many interesting regulatory issues of interest across the world.

Posted at 9:38 pm IST on Tue, 29 Dec 2020 permanent link

Categories: bankruptcy, failure, fraud, investigation

The value of financial centres redux

When I started this blog over 15 years ago, one of my earliest posts was entitled Are Financial Centres Worthwhile? The conclusion was that though the annual benefits from a financial centre appear to be meagre, they may perhaps be worthwhile because these benefits continue for a very long time as leading centres retain their competitive advantage for centuries. At least, most countries seemed to think so as they all eagerly tried to promote financial centres within their territories. But that was before (a) the Global Financial Crisis and (b) the current process of deglobalization.

Yesterday, the United Kingdom finalized the Brexit deal with the European Union, and the UK government rejoiced that they had got a trade deal without surrendering too much of their sovereignty. There was no regret about there being no deal for financial services. The UK seems quite willing to impair London as a financial centre in the pursuit of its political goals. China seems to be going further when it comes to Hong Kong. It has been willing to do things that would damage Hong Kong to a much greater extent than Brexit would damage London. Again political considerations have been paramount.

Decades ago, both these countries looked at financial centres very differently. After World War I, the UK inflicted massive pain on its economy to return to the gold standard at the pre-war parity. In some sense, the best interests of London prevailed over the prosperity of the rest of the country. Similarly during the Asian Crisis when Hong Kong’s currency peg to the US dollar seemed to be on the verge of collapse, then Chinese Zhu Rongji declared at a press conference that Beijing would “spare no efforts to maintain the prosperity and stability of Hong Kong and to safeguard the peg of the Hong Kong dollar to the U.S. dollar at any cost” (emphasis added). The major elements of that “at any cost” promise were (a) the tacit commitment of the mainland’s foreign exchange reserves to the defence of the Hong Kong peg, and (b) the decision not to devalue the renminbi when devalations across East Asia were posing a severe competitive threat to China. In some sense, the best interests of Hong Kong prevailed over the prosperity of the mainland.

Clearly, times have changed. The experience of Iceland and Ireland during the Global Financial Crisis demonstrated that a major financial centre was a huge contingent liability that could threaten the solvency of the nation itself. Switzerland was among the first to see the writing on the wall; it forced its banks to downsize by imposing punitive capital requirements. Other countries are coming to terms with the same problem. Deglobalization adds to the disillusionment about financial centres.

Today, countries are eager to become technology centres rather than financial centres. How that infatuation will end, only time will tell.

Posted at 7:43 pm IST on Fri, 25 Dec 2020 permanent link

Categories: international finance

BIS on Bank of Amsterdam: Pot calling the kettle black

Jon Frost, Hyun Song Shin and Peter Wierts at the Bank for International Settlements wrote a paper last month An early stablecoin? The Bank of Amsterdam and the governance of money which disparages past models of (proto) central banking and new incipient forms of central banking to conclude that the modern central bank is the only worthwhile model. They criticize the Bank of Amsterdam (1609–1820) for its flawed governance that led to its eventual failure, and extrapolate from that to dismiss newly emerging stablecoins which (according to Frost, Shin and Wierts) share the same governance problems. The authors think that, by contrast, modern central banks have the right governance structures and right fiscal backstops.

My biggest grouse with this paper is that if we want to criticize an institution that thrived for 170 years and survived for two centuries, we must compare it against an institution that has been successful for even longer. Unfortunately, I am not aware of even one major central bank today that has been successful for the last 100 years let alone 170 years:

- A large number (perhaps the majority) of modern central banks are less than a century old.

- Most older central banks failed in the 1930s when they abandoned the gold standard and defaulted on their convertibility promises.

- Some old central banks that were not directly on the gold standard (but were pegged to the dollar or the pound) failed when they suspended the peg in the 1930s or during or after the Second World War and did not return to the pre-war parities.

It appears to me to be the height of hubris for an association of failed central banks and central banks that are too young to have experienced failure to point fingers at the Bank of Amsterdam whose track record for 170 years was far better than that of any of these banks. In fact, I think that the Bank of Amsterdam’s track record even at the point of failure was better than the stated goal of most central banks today. The best central banks currently target an annual inflation rate of 2%. Over a period of 200 years, this inflation rate will lead to a 98% loss of purchasing power: 200 years from now, a dollar would be worth only 2¢ in today’s money (1.02 − 200 ≈ 0.02). By contrast, at the point when the French revolutionary armies invaded the Netherlands in 1795, and the true state of the balance sheet of the Bank of Amsterdam was revealed, the money issued by the Bank of Amsterdam fell to a 30% discount to gold (Frost, Shin and Wierts, page 24). In other words, over the two centuries of its existence, the money issued by the Bank of Amsterdam lost only 30% of its value for an annual depreciation of less than 0.2% (1.0021609 − 1795 ≈ 0.7). At the point of failure, the performance of the Bank of Amsterdam was equivalent to an annual inflation rate one-tenth that of what the best central banks promise today.

If modern central bankers think that they are better than the Bank of Amsterdam (either in its heyday, or on average over its entire life including the point of failure), they need to introspect long and hard whether they suffer from excessive over confidence or amnesia.

Posted at 6:20 pm IST on Thu, 17 Dec 2020 permanent link

Categories: crisis, financial history

Bankruptcy hardball and bank dividends

When I read the recent BIS working paper Low price-to-book ratios and bank dividend payout policies by Leonardo Gambacorta, Tommaso Oliviero and Hyun Song Shin, I was immediately reminded of the paper Bankruptcy hardball (Ellias and Stark (2020), Calif. L. Rev., 108, p.745) though that is not how Gambacorta, Oliviero and Shin analyse the issue.

Ellias and Stark documented the tendency of distressed firms to declare dividends or otherwise move assets out of reach of the creditors for the benefit of shareholders. This strategy which they called bankruptcy hardball is most closely associated with private equity owners.

As I reflected on the Gambacorta, Oliviero and Shin paper, it struck me that what makes bankruptcy hardball attractive is the high level of leverage rather than private equity ownership. If the assets are worth 100 and debt is 80% of assets (so that equity is 20%), then shifting 10 of assets to the shareholders reduces the value of debt only by 12.5% but increases the value of the shareholders by 50%. If debt is 90% of assets, then the same shift of 10 would be only a 11% loss to lenders but a 100% gain to shareholders. Since private equity is characterized by high leverage, the incentives are much greater in their case. On the verge of bankruptcy, it is true that the leverage would shoot up for all companies (as the equity becomes close to worthless), and it might appear that every firm can play hardball. However, the tactics are more likely to survive legal challenges when they are implemented at a time when the company appears to be solvent, and ideally years before a bankruptcy filing. So the greatest opportunity to play hardball is for those companies that have high levels of leverage in normal times when they are still notionally solvent but possibly distressed.

Apart from firms owned by private equity, there is another example of a business with high levels of leverage in normal times - banking. Banks typically operate with leverage levels that exceed that of typical private equity owned businesses. One would therefore expect banks to also play the hardball game - pay large dividends when they are distressed but still notionally solvent. And that is what Gambacorta, Oliviero and Shin find.

Their key finding is that banks with low Price to Book ratio (the ratio of the market price of the share to the book value per share) tend to pay higher dividends and this tendency becomes even more pronounced when the Price to Book ratio drops below 0.7. Price to Book has been associated with financial distress in the finance literature since the original papers by Fama and French. But the link is even stronger in banking where a low price to book ratio is often driven by the market’s belief that the asset quality of the bank is a lot worse than the accounting statements indicate. In other words, while for non financial companies, a low price to book reflects low profitability, for banks, it often indicates that book equity is overstated (due to hidden bad loans) and the capital adequacy of the bank is a lot worse than what the accounting statements suggest. Price to book is therefore an even more direct indicator of distress for banks than for non financial companies.

For a bank which is already highly levered and whose true leverage is even higher because of overvalued assets, dividends become an attractive device to transfer value to shareholders from creditors. The fact that the bank meets the capital adequacy standards set by the regulators (aided by overvaluation of assets) acts as a cover for the hardball tactic. The fact that many creditors (especially the depositors) are protected by deposit insurance means that creditor resistance is muted.

Gambacorta, Oliviero and Shin talk about the wider social benefits of curtailing dividends (increasing lending capacity), but there is a more direct corporate governance and prudential regulation argument for doing so. Regulators have already recognized the role of market discipline in regulating banks (Pillar 3 of the Basel framework). From this it is a short step to linking dividend and other capital distributions to a market signal (price to book ratio).

Posted at 5:46 pm IST on Thu, 10 Dec 2020 permanent link

Categories: bankruptcy, corporate governance

Negative beta stocks: The case of Zoom

One of the questions that comes up every time I teach the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) in a basic finance course is whether there are any negative beta stocks, and if so what would be their expected return. My standard answer has been that negative beta stocks are a theoretical possibility but possibly non existent in practice. Every time I have found a negative beta in practice, there was either a data error or the sample size was too small for the negative beta to be statistically significant. I would also often joke that a bankruptcy law firm would possibly have a negative beta, but fortunately or unfortunately, such firms are typically not listed. (The answer to the second part of the question is easier, if the beta is negative, the expected return is less than the risk free because it hedges the risk of the risk of the portfolio and one is willing to pay for this hedging benefit).